I first saw the name Michael Richards completely by chance at a retrospective of his work called Michael Richards: Are You Down? at the Bronx Museum. A few minutes into the visit, I realized that he had been killed in the 9/11 attacks. Monika Bravo, another artist at the studio, remembered that Richards often stayed late, working into the night, and that she had left him alone there on the evening of September 10th, watching Monday Night Football.

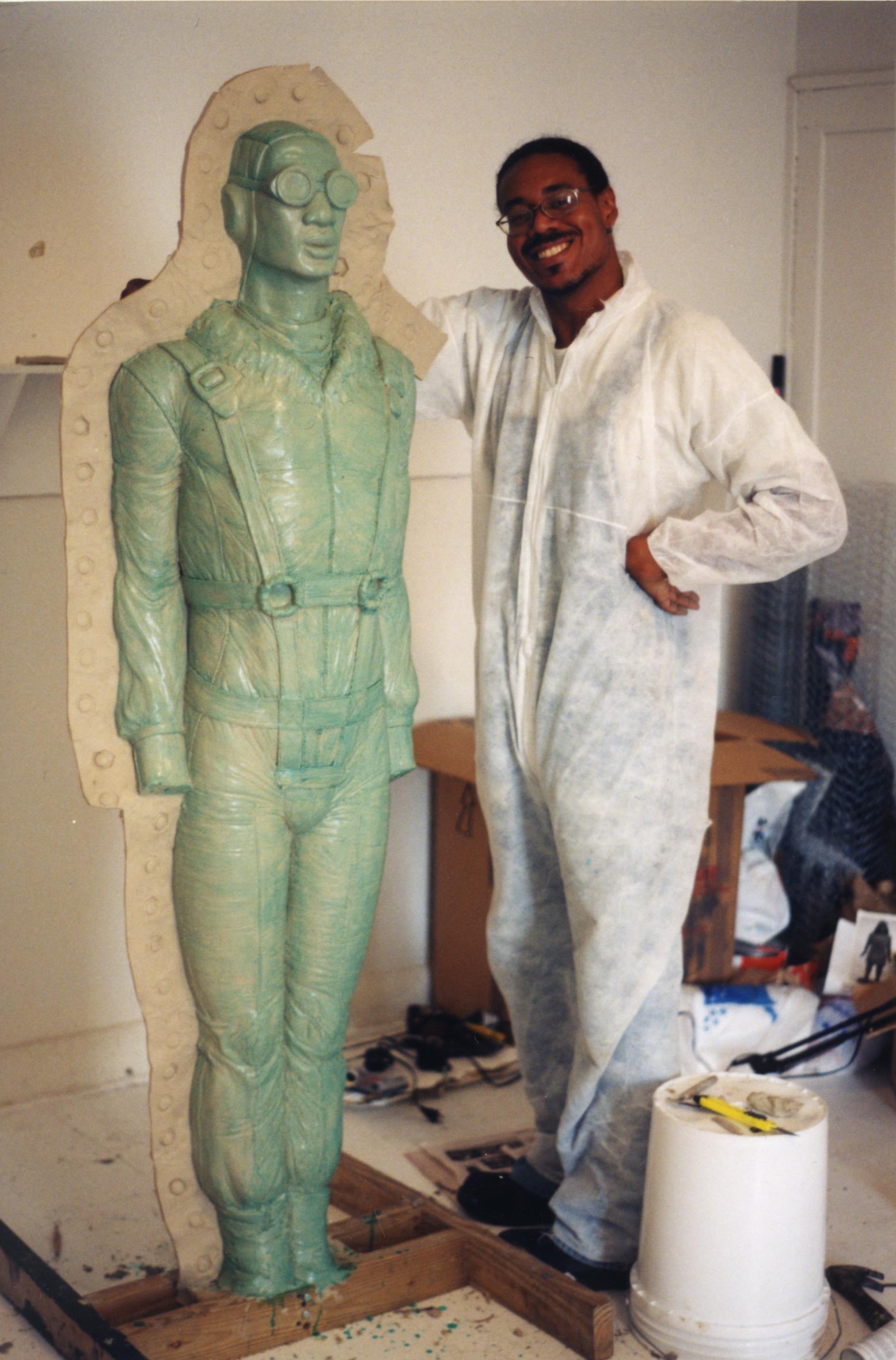

A Black sculptor born in Brooklyn and raised in Kingston, Jamaica, Richards was an artist with an obsessive focus on aviation. He took a particular interest in the Tuskegee Airmen, the all-Black group of pilots who served in the segregated U.S. military. His work depicts WWII-era fighter planes crashing through the bodies of Black pilots, who sit in deathlike repose slumped against each other. Planes hang from the ceiling, painted in black and frozen in a state of falling. Using his own likeness for the sculptures, he places himself, his own life, within this dialogue between race, flight, and escape. There is also an inescapable feeling of violence and terror: WWII, police and state brutality, racial discrimination.

Exemplifying that feeling is "Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian," a nearly seven-foot gilded steel figure, suspended in the air with a metal pole and dressed in a WWII pilot’s helmet and uniform. The body, a cast of Richards’s own, is covered in arrow-like planes piercing his torso and shoulders, recalling the story of the Christian martyr St. Sebastian, who was condemned to death first by arrows and, surviving that, by beating. “Tar Baby” descends from a 19th century folktale in which a fox tries to trap a rabbit using a doll made of tar as bait. Today the term is a racial slur. The references are placed in opposition to each other, while simultaneously enacting a synthesis: the saint-like pilot, eyes closed as if asleep, dead, or in prayer, covered in impact wounds from miniature planes that have riddled his body like bullets, a gesture that connects the work to America’s long history of police brutality. High-profile cases like the beating of Rodney King in 1991 and the killing of Amadou Diallo in 1999 would have been fresh on Richards’ mind. The artist imagines his own death like that of Diallo, who was shot 19 times by officers in a case of mistaken identity. Richards completed the sculpture in 1999. Among the unfinished works in his World Views studio space was its twin, in silver.

As an interpretive guide giving tours of the Memorial Plaza, I sometimes detour around the entire North Pool. This is where visitors see the names of victims from Cantor Fitzgerald, Marsh & McLennan, and hundreds of other brokerages and firms alongside those from Flight 11, Windows on the World, and 1993 World Trade Center bombing. On the north side of the pool, among the financial analysts, broadcast engineers, and maintenance workers, is the artist Michael Richards' name.

When you learn the story behind that name, there is suddenly an indelible link between you and this person who died here, much like the feeling you get walking through a cemetery. Richards' name now seems to lift from the bronze and take on a life of its own. This is the hope of a memorial: that these names — these links to their stories — are not only un-erasable but that they touch our minds and hearts, holding space in our memories. I think, on my best days, my work here as a guide is simply to carry a little piece of that hope forward.

By Miguel Coronado, Interpretive Guide, Education