Make a donation to the Museum

Rescue & Recovery: In Their Own Voices with John Ryan, PAPD

Rescue & Recovery: In Their Own Voices with John Ryan, PAPD

- June 29, 2022

Throughout May, when we marked the 20th anniversary of the formal end to rescue and recovery operations at Ground Zero, we published a series of Q&As with those involved in the unprecedented clean-up efforts. To continue highlighting the diversity and previously unimaginable undertaking of the 9/11 rescue and recovery community, we've created an ongoing monthly series entitled "In Their Own Voices." In this first installment, the Port Authority Police Department's John Ryan tells us about his involvement and shares his perspectives more than two decades later.

Where were you on 9/11?

I had been with the PAPD for 22 years, spending most of my time in Times Square. My connection to the World Trade Center though, goes back to before I became a police officer. It dates to 1977 when I was in college and worked as a guide at the Observation Deck of the South Tower. I had a good understanding of the buildings and the surrounding area. However, soon after the attacks when I was at the site, I was looking for all the things in my memory as a point of reference, but with all the devastation, it was impossible to know exactly where you were. I was in disbelief that I was even at the World Trade Center site.

On September 11, 2001, I was originally scheduled to work and meet with an undercover officer, not too far from the World Trade Center, but it was my daughter’s first day of pre-school and my wife didn’t think I would make it home in time if I went into work, so I took the day off. Sometime after I had gotten up that morning, I received a call from my sister-in-law who said a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. I put on the news, and shortly thereafter, the second plane crashed. I realized we were under attack. At that point, I started to make my way into the city, finding the roads had been closed. I made my way to Kennedy Airport and then down to the site. Both buildings had already collapsed.

As a police department, we were in a lot of chaos after the collapse of the buildings, having lost our Superintendent of Police, Fred Morrone, and many of our officers. Additionally, the World Trade Center was the headquarters of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which the police department was a part of. Many Port Authority employees were killed that morning, including our Executive Director, Neil Levin. We were in upheaval, not only having suffered the attack but having lost a great deal of our go-to people. As an agency responsible for the airports, tunnels, bridges, and all key transportation facilities that would keep New York running, we had a lot to do. One of the most important tasks was putting together a team of people that would stay at the World Trade Center and handle the rescue, and then recovery operation. I was one of the people that was selected for that. We organized at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, where we met up with other PAPD officers at other commands. We organized search teams of ten officers, and on designated shifts and hours, we responded to the World Trade Center site.

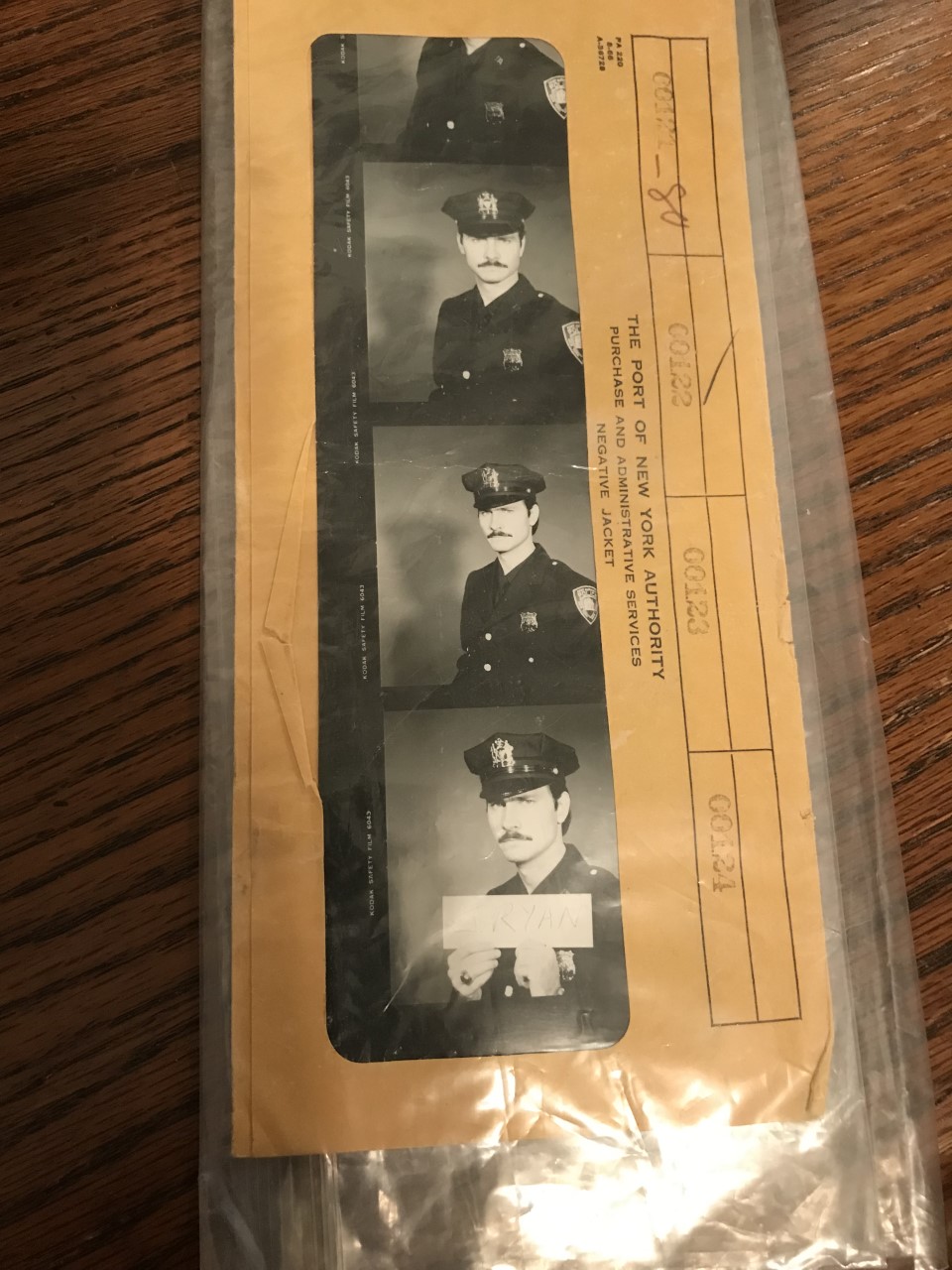

A strip of photos from the Port Authority's archives, showing Ryan at his police academy graduation and found intact at Ground Zero.

What role, if any, did you play in the rescue, recovery, and relief efforts?

I spent the next nine months at Ground Zero as the Day Tour Commander of the Rescue and Recovery Operation. Initially, I oversaw the rescue of potential survivors. The rescue, however, quickly turned into a recovery operation. I was interacting with family members, providing security for dignitaries that came to visit the site, and attending daily meetings with all the entities that worked at Ground Zero. This included the trades, construction workers, truck drivers, DSNY, PAPD, and NYPD. We tried to take baby steps, coming up with goals for the next 24 hours and reviewing the past 24 hours. It was a 16-acre site and coordination was key to ensure everything possible was done to protect the dignity of the people that were lost. We also had to ensure the safety of the people working on the site.

One of the most difficult things we had to do was recovering the individuals we worked with and seeing them in that condition, some only recognizable by their name tags or the serial numbers on their weapons. It was odd. We would move into some areas, and nothing would survive. The fires had been burning for so long and the heat was so intense that anything that had been there would have turned into ash. Then, we would move five feet away and find things perfectly intact. On one day, as we moved to the lower portion between the North Tower and Building 6, we found many photographs of New York City. As it turns out, the Port Authority had a large photo archive of things around the city and kept them in a storage area underneath the site. We discovered many of these photos still intact. One particular photo found by one of my officers was of me – at my graduation ceremony from the Port Authority Police Academy. Of the millions of tons of debris, this was handed to me.

Can you describe the bond between yourself and other recovery workers? How has this community impacted you?

There is a quote on a wall in the Museum from recovery worker Joe Bradley that sums it up: “We came in as individuals. And we’ll walk out together.” We developed bonds with people at the site that we normally wouldn’t have been working as closely with - the trade unions, the iron workers, the grapple operators. The closeness between the NYPD, PAPD, and FDNY came about because all three departments suffered tremendous losses, and also because members of the department lost family members that day.

It felt like one long day. We were there for so many hours. When human remains were found, they would be placed in a bag, draped in an American flag, and carried out by a group of workers. Performing this ceremony hundreds of times created a bond between us that you would never experience under any other circumstances.

What does May 30th mean to you?

Going at that pace for such a long period of time, day in and day out, I don’t think we were prepared that someday it would end. In March we tried to establish an exact timeline, which was not an easy thing to do. We assessed the project based on the amount of material that remained on the site that needed to be sifted through, how many truckloads we estimated it to be, and the number of trucks that were leaving each day. In doing this, we came up with the date of May 30th. This would be declared the closing day of the rescue and recovery operation.

We also decided to hold a "Workers Day" ceremony on May 28. This is when we would cut down the final steel column and prepare it for its exit two days later. That day, around what would’ve been the change of tours, we worked two 12-hour shifts, and brought all the workers down. We all surrounded the final column, and the crane was brought over. Each iron worker was able to cut about an inch of the column. Then it was lifted and lowered onto the flatbed truck and covered in a large American flag and a large bouquet of flowers. At that point, it was prepped to be driven out on May 30.

We had been operating at such a fast pace, but for that brief moment when I took a step back, I realized all that had been accomplished. However, I also realized just how many people had still not been identified or accounted for.

Do you have any health issues connected to your time at Ground Zero?

Over the past 20 years, I’d been focused on helping other people that had worked for me or had participated in the rescue and recovery operation and never really focused on myself. But after 43 years on the job, and likely retiring in the near future, I’ve started to focus on my health and get checked out. I’ve found some issues that I’ve had to deal with.

To the generation who is growing up with no memory of September 11th, why is it important to share your story and the stories of others with them?

I was on the job not only for the events on 9/11, but also the first attack in 1993. Amazingly, a lot of people are not aware of 1993. They’re not aware of the loss of life, the injuries, and the damage that was done. It reinforces the need for us to tell people about what occurred and what the impact of the loss of life was. Also, the bravery of the people that responded to the attacks and the camaraderie they formed.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Just as it’s important for us to share the experiences of responding on 9/11 and the nine-month rescue and recovery operation, it's also important in recognition of those that have health issues from their exposures at Ground Zero, to share and educate others on how they can operate safely and best practices to protect people from possible exposures.

When 9/11 happened, everybody came to help with the best of intentions, but given how many people have health issues as a result of this, it's alarming. If we don’t ensure we take lessons learned from this to protect people who may be in these types of environments, we have learned nothing.

Compiled by Caitlyn Best, Government and Community Affairs Coordinator

Previous Post

Art Cart Returns to Memorial July 6

We're thrilled to announce the return this summer of the Art Cart, offering visitors with children free self-guided activities that shed light on the story of 9/11 and uncover unique design elements of the Memorial Plaza.

Next Post

Memory of Museum Inspires Young Visitor

A letter from a family that recently visited us shares the unexpected response the Museum prompted in their autistic daughter.